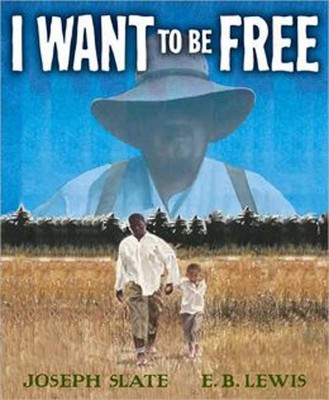

Year Published: 2009

Written by: Joseph Slate

Illustrated by: E.B. Lewis

Description

Before I die, I want to be free. But the Big Man says, You belong to me.

A runaway slave has broken the chains that bound him, but as he sets out for the land of the free, he still carries the weight of an iron ring around his ankle. As long as it remains, and as long as the Big Man hunts him, he’ll never truly be free. But rescuing an orphaned slave child from certain capture gives him the strength to keep moving on, and miraculously, the child’s love and gratitude are all that is needed to destroy the shackle once and for all.

This moving, poetic text is based on a story from the sacred literature of Buddha.

From Publishers Weekly

Transposing a Buddhist story he encountered in Rudyard Kipling’s Kim, Slate (the Miss Bindergarten series) moves the setting to the antebellum South and casts as speaker an escaping slave who rescues an orphaned, ill slave child. Forced into rhymed couplets, the language strains between the demands of the rhythm and dialect—when the slave reaches the camp of gone-free men, they advise him to abandon a child he hears cryin,’ saying, Let the Big Man come. Take him back./ He has the farm. Food we lack. For this scene, Lewis (Coming on Home Soon) contributes extraordinarily accomplished watercolors: the scrim of night lets through the escaped men’s white shirts, a hint of their profiles, the sick child’s face. A religious denouement is portentous without being satisfying. Safely in the Land of the Free, the child touches the shackle on the speaker’s leg that no one else has been able to remove, and It fell away. In the most sentimental of his paintings, Lewis (Coming on Home Soon) pictures a single tear on the man’s face: How, dear child, did you set me free?—I’m from the Lord. You cared for me. Ages 6–8.

From School Library Journal

Kindergarten-Grade 4—A young escaped slave on the run is the focal point of this book loosely based on Rudyard Kipling’s Kim. A powerful refrain is heard throughout this story and becomes a mantra for the protagonist, who dreams only of freedom: “Before I die, I want to be free. But the Big Man says, ‘You belong to me.'” After he is recaptured, a ball and chain is attached to his ankle, making it crystal clear that he is owned by another. He manages to break the chain and leave the ball behind, but the shackle itself remains firmly in place on his ankle. Along his escape route he stops to care for an orphaned child and, in the end, it is this child who frees him from the shackle. The verse, in rhyming couplets, is not as strong as the idea it is attempting to convey. Rather than a lyrical song, the text comes across as choppy and somewhat pedestrian. In contrast, Lewis’s beautiful watercolors lift this book to the level it was meant to achieve. The palette is dark as the young slave travels mostly through the night toward freedom, and the colors brighten as the child frees him from his bonds and his world opens up. This is another book to add to the corpus of Underground Railroad stories.—Joan Kindig, James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA