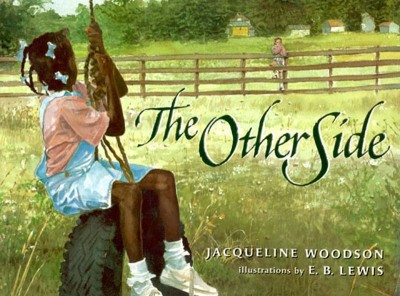

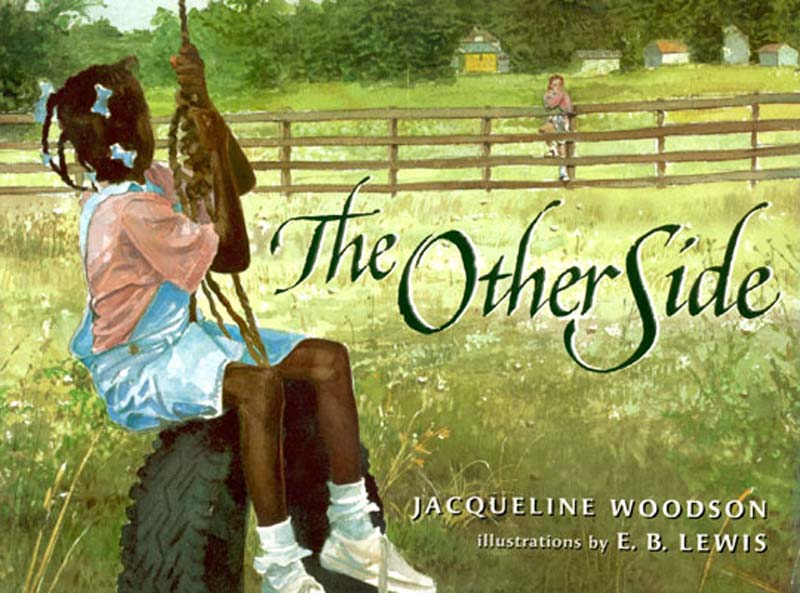

Year Published: 2001

Written by: Jacqueline Woodson

Illustrated by: E.B. Lewis

Description

Publishers Weekly

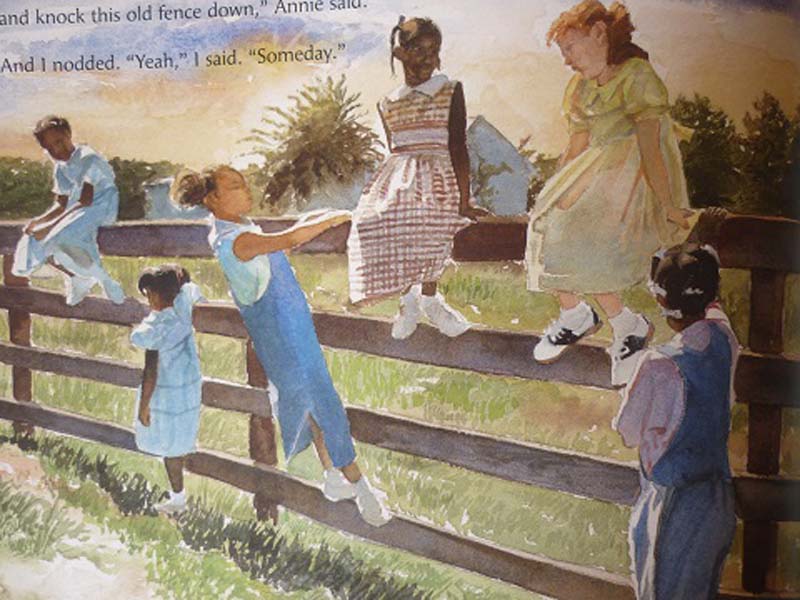

Woodson (If You Come Softly; I Hadn’t Meant to Tell You This) lays out her resonant story like a poem, its central metaphor a fence that divides blacks from whites. Lewis’s (My Rows and Piles of Coins) evocative watercolors lay bare the personalities and emotions of her two young heroines, one African – American and one white. As the girls, both instructed by their mothers not to climb over the fence, watch each other from a distance, their body language and facial expressions provide clues to their ambivalence about their mother’s directives. Intrigued by her free-spirited white neighbor, narrator Clover watches enviously from her window as “that girl” plays outdoors in the rain. And after footloose Annie introduces herself, she points out to Clover that “a fence like this was made for sitting on”; what was a barrier between the new friends’ worlds becomes a peaceful perch where the two spend time together through out the summer. By season’s end, they join Clover’s other pals jumping rope and, when they stop to rest, “we sat up on the fence, all of us in a long line.” Lewis depicts bygone days with the girls in dresses and white sneakers and socks, and Woodson hints at a bright future with her closing lines: ” Someday somebody’s going to come along and knock this old fence down.,” says Annie, and Clover agrees. Pictures and words make strong partners here, convincingly communicating a timeless lesson.

The Bulletin

Books about race and race relations, whether well-written or not, are books that carry tremendous historical and political baggage, and they are nearly guaranteed to provoke strong emotions of one kind or another. The topic of racism is difficult to serve up in palatable portions for younger listeners and readers, who have limited ability to provide their own context. Informed by the adult perspective of the writer, these books tend toward over-explanation in an effort to provide their own context. Informed by the adult perspective of the writer, these books tend toward over-explanation in an effort to provide that context; they are often message-driven, with neat conclusions and the assumption of simpler, happier futures. Oversimplification of complex issues is a charge often leveled at picture books dealing with weighty subjects; it is a charge that cannot be leveled at Jacqueline Woodson’s latest book. The title of Woodson’s Evocation of a not-so-long ago summer refers to a seemingly impassable division: “that summer the fence that stretched through our town seemed bigger. We lived in a yellow house on one side of it. White people lived on the other.” Clover an African-American girl about eight or nine years old, relates the story of the “summer there was a girl who wore a pink sweater,” a white girl, on the other side of the fence. After weeks of watching one another, the two girls finally speak, and, with the pragmatism of children, find a way around their mothers’ injunction that they stay on their own side: ” A fence like this is made for sitting on,’ Annie said. She looked at me sideways. ‘My mama says I shouldn’t go on the other side,’ I said. ‘ My mama says the same thing. But she never said nothing about sitting on it.’ ‘ Neither did mine,’ I said. That summer me and Annie sat together on that fence.” Woodson is a writer of exceptional integrity, and this short story contains the same emotional and moral complexity found in the author’s longer work (Miracle’s Boys, BCCB 5/00; If You Come Softly, BCCB 10/98) distilled into a minimalist yet poignant read aloud. Clover tells the story that she knows, the story of that particular summer and that particular fence, from her particular point of view. It is specificity that make the tale so effective and that sets the unstated context into bold relief. Lewis’ watercolors provide a telling backdrop to the actions; rural settings is suggested more than delineated, and the gentle softness of the summer light helps model both landscape and characters. Perspective and the placement of characters in the compositions physically establishes the distance between the two girls, each on her own side of the fence. The body language of the children is also telling. In one spread, Clover’s Friends jump rope near the fence where Annie watches. Annie, asking to play leans hopefully over the rails of the fence visually foreshadow the final text; “when we were too tired to jump anymore, we sat up on the fence, all of us in a long line ‘Someday somebody’s going to come along and knock this old fence down, ‘ Annie said. And I nodded ‘yeah,’ I said, ‘Someday.’ This is an emotionally intricate tale presented simply and intimately and the open-ended conclusion unselfconsciously encourages discussion, examination, and inquiry. Unlike authors of other picture books dealing with racism and prejudice, Woodson doesn’t over explain or stack the emotional deck. She doesn’t knock the fence down for the reader/listener; the town does not suddenly have a collective change of heart. She just lets Clover tell the story, and then she leave it up to readers and listeners to resolve any questions that remain.

Booklist

Ages 5-8 like her novel I Hadn’t Meant to Tell You This(1994), Woodson’s picture books tells a story of a friendship across race. Lewis’ Beautiful watercolors show a middle-class pre-civil rights setting, in which young girls wear pretty dresses, and there’s a brown picket fence-in almost every picture- that divides the blooming green fields. Clover tells the story. She lives in a big yellow house on one side of the fence. Annie Rose live on the other side, the white side. Their mothers say it isn’t save to climb over. First the girls sit together on the fence, getting to know each other and watching the whole wide world. Then one day Annie Rose jumps down to join Clover and her friends jumping rope. Even young children will understand the fence metaphor and they will enjoy the quiet friendship drama. One unforgettable picture shows Clover and Annie Rose in town with their mothers’ the white-gloved adults pass one another without seeing, but, the girls turn around and look back with yearning across the sidewalk lines. All the pictures have that sense of longing; it’s in the girls’ body language (their arms reaching out) and in the landscape with its ever-present barrier. At the end, as Clover, Annie Rose, and the other girls sit together on the fence, Drooping and tired after their game, they are sad; they want the fence to come down – Hazel Rochman